Child labour: Uganda’s teachers are crucial agents of positive change

The sensitisation programme of the Uganda National Teachers' Union has borne great fruits against child labour in a remote district, leading to a substantial increase in the enrolment and retention of students, girls and boys alike.

The Uganda National Teachers' Union (UNATU) programme against child labour in Erussi, close to the Congo border and located a nine hour drive from Kampala, and the second poorest district in Uganda, has changed the mindsets of parents and teachers towards education and child labour.

The main activities children are engaged in in Erussi are domestic work - helping siblings and elders at home - , farming and selling products at the markets, fetching water and doing all kind of chores for the family. Children also take part in long festivities and dowry (at least 4 days), disco dancing, drugs and prostitution, and orphans and disabled children are particularly vulnerable.

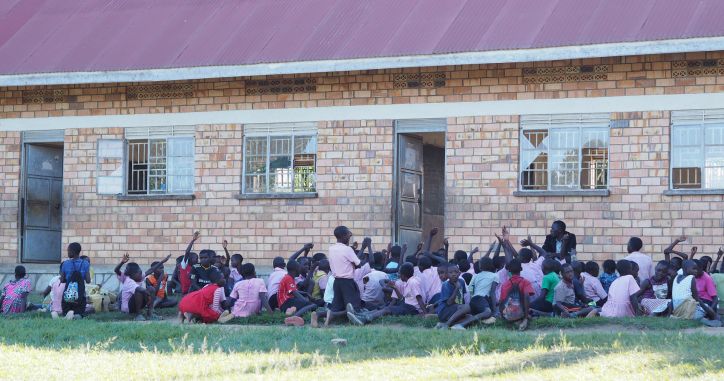

But at the Oboth primary school, following the introduction of the union programme, the school population has risen by 13%: 118 new children, girls and boys, enrolled in February. And two months into the new schoolyear, not a single one has dropped out.

Teachers’ commitment in fighting child labour

Teachers acknowledge that the programme allowed them to be better prepared to face the plague of child labour and better interact with their students.

“We feel now better equipped to identify the children who are at labour risk,” said Mr. Richards, a teacher in Oboth, adding: “My teaching has improved, I have a better pedagogy and I can feel that children enjoy school more. They are happier.”

“I feel more motivated through the union awareness sessions, and I have understood that I can act as role model,” echoed Joyce Marachtho, the only female teacher in this rural school. “I witnessed that teachers develop increased empathy for the children and they built a relationship with the parents out of concern for the children,” further underlined the proud headmaster Claudius Okec.

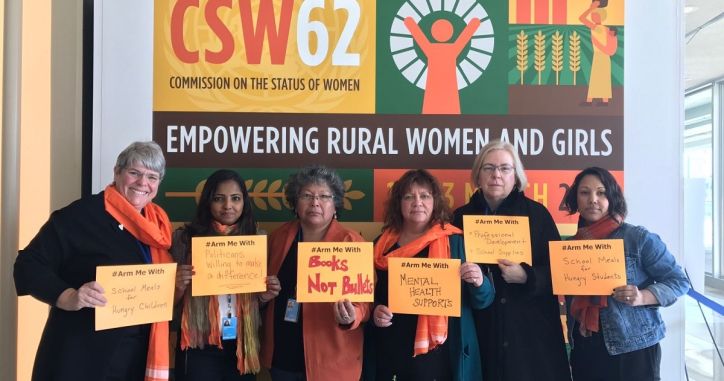

This highly successful UNATU programme belongs to the “child labour free zones” project, promoted by Education International (EI) through Dutch funding provided by the Stop Child Labour Coalition and FNV Mondiaal, and aiming to support education unions in training school leaders and teachers, organising awareness raising activities towards local political leaders, community and religious chiefs, parents and education stakeholders and advocacy activities to get additional funding for education.

“We have ignited the fire and should not look back to let it die out," says James Tweheyo, General Secretary of UNATU. "The smiles we have put on the faces of these children, especially those who had dropped out, shall give testimony of the open hearts and hands of Educaiton International and her partners.”

After three years, the local project in Erussi is a success and almost sustainable. Teachers in eleven public schools have been trained, school leaders hold daily registries of school attendance, schools have been equipped with sport and art minimal equipment, parents have joined income savings initiatives (to cover school costs), in some villages income generating activities have been launched, school clubs reach out to children not in school.

Cost of education, a child labour factor

Programme participants have also clearly identified the cost of education as being a key issue leading to child labour. While education is free since Uganda cancelled school fees in primary education in 1997 – and in secondary education in 2007 – , parents have to cover for the cost of uniforms, books and scholastic material. It is estimated that a schoolyear costs 100,000 Ugandan shillings per child (around 27 USD). Parents have to be convinced that education is a good investment of scarce resources. Sometimes, children also feel guilty that parents have to pay school costs and they drop out.

“Changing the mindsets is vital to have a sustainable eradication of child labour and in Uganda, as elsewhere teachers are agents of change,” says Tweheyo.

Quality school environment for quality education

The project brings other hard education challenges to the forefront, accounting for the estimated 1,500 children still out there without education in Oboth, according to the parents’ association. There are insufficient teachers and equipment to meet the growing classroom population: too few classrooms, hardly any latrines and sanitary equipment, no water, no meals.

In the first grade, we have over 360 children for one classroom, detailed the headmaster Okec, reminding that the official teacher ratio in Uganda is 1/55.

“We had to remove all the desks and chairs to allow all children in,” he deplored. “The teacher is pushed in a tight corner, with no space to move to the blackboard. Providing child centered learning is impossible in those conditions. In principle we are entitled to 6 teachers for the first grade, but we only have two. The local education authorities know of the needs. There is no lack of trained teachers but administrative decisions are slow to be processed. There is a need for additional teaching space. The community has come together to build new latrines and a teacher house, but it is risky to start erecting classrooms, it is not safe.”

UNATU continues to lobby for the government to provide adequate resource to education, aware that the education budget has been fluctuating from 16.8% in 2011 to 11% in 2015/16.

Water, hygiene and food are also constant challenges, he also condemned, lamenting that there are 5 latrines for girls and 5 for boys, for over 1,000 children.

Some children arrive at 7am with an empty stomach. Only six out of ten children can go home during the lunch. The others do not have time to cover the few kilometers back home during the 90-minute break, and few have been given a lunch pack.”

The parent-teacher associations and school clubs – composed of pupils and teachers – monitor school attendance and visit parents whose children have missed out. “We discuss, we try to understand what is at stake, Richards says, believing that “it is often cultural,” that some parents thinking that they “produce” children to help them out with many chores.

Pointing out that the rights of children is “a new concept that needs to be explained”, he recognised that “once convinced by the merits of education for the wellbeing of the child and the family, parents are usually enthusiastic supporters”.

Caption:

proud headmaster Claudius Okec