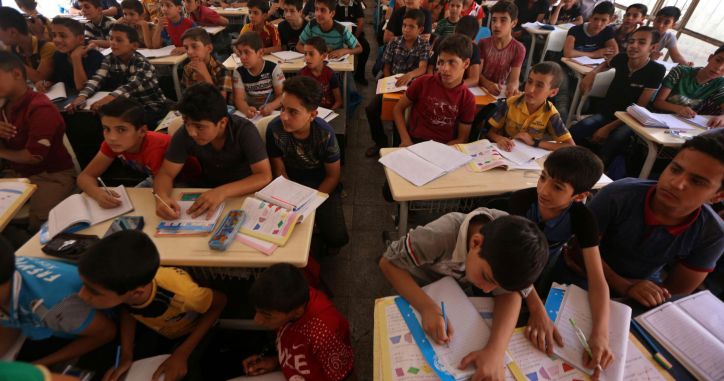

1.7 million more teachers needed to deliver EFA by 2015

On 25 September, the Global Campaign for Education (GCE) and EI launched a new report identifying severe primary teacher gaps in 114 countries, undermining efforts to achieve the UN Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of Education for All (EFA) by 2015.

As part of the new campaign, Every Child Needs a Teacher, GCE and EI co-hosted in New York, USA, a launch event with speakers including former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown MP, now United Nations (UN) Special Envoy for Global Education, Amina J. Mohammed, UN Special Adviser on Post-2015 Development Planning and Irina Bokova, Director-General, UNESCO. The campaign focuses on the plain fact that without trained teachers for all, there will never be EFA

The report, Every Child Needs a Teacher: Closing the Trained Teacher Gap, highlights some of the shocking realities behind the reported data:

• In Mali, only half of all primary school teachers are trained – and only a quarter of these have had training lasting six months or longer

• Some countries count those who have completed primary school and a one-month training course as trained

• A third of countries report that no more than half of their pre-primary school teachers are trained - with the worst situations including Chad, which has just one pre-primary teacher for every 1,815 children of this age group

• Thirty one countries report that fewer than three quarters of teachers are trained (to any accepted national standard)

• Niger had just 1,059 trained lower secondary school teachers in 2010 – compared to 1.4 million children of lower secondary school age – meaning only one trained teacher for every 1,318 children.

The report is available in full here

“The crucial role played by teachers in providing quality education is often emphasised,” EI President Susan Hopgood said. “But, do national governments and the international community really live up to such a commitment? All too often, we see that good intentions are overruled by cheap solutions and cost-cutting measures. But: Every child has the right to be educated by a qualified teacher. Moreover, investment in quality education has a very high multiplier effect: every good teacher benefits an entire class, year after year, and when those better-educated students become parents, they will likely demand a good education for their children, further strengthening society in general.”

She went on to say: “EI is proud to launch today with the GCE to call attention to the trained teacher gap. Every Child Needs a Teacher. Every child has the right to a quality, publicly delivered education. These are true and still largely aspirational statements. For EI and its members, 30 million teachers around the world, the two go hand in hand and we will work to realize them over this next year.”

Every child’s right to an education will amount to very little if we do not urgently address the issue of the trained teacher gap, Hopgood warned. “Every child’s right to education will not be realised if we are unable to address the issues of equity and quality.”

She underlined that the world community must urgently focus on the recruitment of over 2 million more qualified teachers and the improvement of the competences, knowledge and skills of practising teachers if we are to achieve the EFA targets and MDGs (access, equity and quality) by 2015.

Hopgood further stressed: “From our launch with GCE, to our pedagogical movement, to our Summits on the teaching professions with OECD, to our work within the Global Partnership for Education; with UNESCO and ILO on social dialogue, to Global Action Week and World Teachers’ Day, together with our members and partners at local, national, regional and global levels, we are committed to driving this campaign into every forum and space we can.”

GCE and EI are making several recommendations, based on the evidence of countries which have already made good progress towards closing their own national teacher gaps.

They urge governments worldwide to: develop realistic, costed workforce plans to meet the full gap in trained teachers and deploy those teachers equitably, as well as develop and enforce high national standards of training; ensure that all teachers are being paid a decent, professional wage; and allocate a minimum of 20% of national budgets, or 6% of GDP, to education, and ensure that at least 50% of this is dedicated to basic education, with a much higher percentage where necessary.

Also, bilateral donors should: meet their commitment to spend at least 0.7% of GNI on aid; realign official development assistance to commit at least 10% to basic education, including contributions to the Global Partnership for Education and a proportion of budget support; and develop and publish a plan setting out contribution to tackling the teacher crisis and lowering Pupil-to-Trained-Teacher ratios, and report annually on progress against this plan.

The World Bank on its side should: meet its original 2010 pledge of additional funding for basic education by providing at least $6.8 billion for basic education in international development assistance countries between 2011 and 2015, and an increase in funding for sub-Saharan Africa; and refrain from providing advice or conditionality that limits the professional status, training, pay or unionisation of teachers, or that encourages high-stakes testing.