France: a profession in search of confidence

The education system has become a topic in French political discourse these last six months: with the Presidential election, consultations on the status of the education system in a society in crisis, it is the future of generations to come that is at stake when education is broached. The economic crisis requires enhanced preparation for future citizens as well as daring solutions to meet the challenge of academic democratisation which has broken down in France. Primary school is a priority so that children can start learning from the earliest age.

A highly professional occupation

The challenge cannot be taken up without teachers who are endeavouring tirelessly to give instruction in the classroom a more complex dimension. How can all students make progress through the rationale not of a simple task but of thinking and constructing knowledge? How are we to deal with weaker pupils, with school failure and the refusal to learn? How can the new knowledge that the school must take charge of be integrated: learning a living language, new technologies, sustainable development? How can children with disabilities be integrated optimally?

What is to be done? This list gives an idea of the professional dilemmas that teachers face every day. Such difficulties are exacerbated in France by the solitary exercise of the occupation that leaves teachers to cope with their difficulties to the point of personal lapse and malaise at times. The growing weight accorded to assessments in the last five years has given the impression that the profession could be reduced to applying a “diagnosis-remediation” rationale to each pupil in each case. But too much assessment means less learning.

More difficult working conditions

Teachers have to deal with the growing complexity of their profession under increasingly difficult conditions with larger classes. The policies pursued in recent years in France were guided by short-sighted rules and the successive measures and reforms initiated by the Ministry of National Education were synonymous with abnegation.

This year primary school system is faced with 4,600 job cuts, including 1,407 classes closed, 1,949 fewer specialised teachers, with 864 replacement positions, 100 training instructors, 103 educational consultants and 460 priority education support positions done away with. Nearly 80,000 positions have been cut in national education in five years.

According to the OECD, France is at the bottom of the league of member countries when it comes to the ratio of staff to students (five to 100), far behind Portugal, Greece and Spain, but also Sweden, Belgium or Austria, countries where the rate fluctuates between six and 10. In 2011, the OECD also indicated that the country invested 14 per cent less than the average of OECD member countries, and that the statutory salary of primary and secondary school teachers with at least 15 years of experience declined in France between 1995 and 2009.

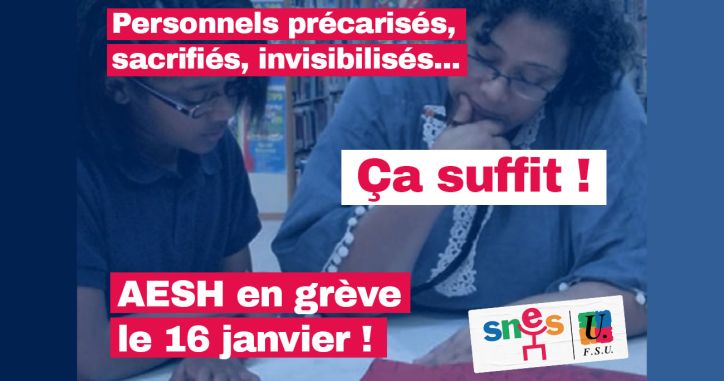

In spite of this terrible litany, teachers have continued to do their job. In spite of the pitfalls, they have provided schooling for children with disabilities pursuant to the Act of 2005. There were 210,395 pupils with disabilities in the classroom in 2011 compared with 153,361 in 2006. Primary school teachers started teaching foreign languages, initially as an introductory programme and then as fully-fledged courses, but without having commensurate training for the task. Another example pertains to the new digital tools. With the IT plan for all in 1985, and the rural digital plan in 2009, the State took action late and with insufficient support. This deficiency did not prevent many teachers from transforming their practices by relying on self-training and exchanges with their colleagues. Furthermore, opinion polls* showed that a large majority of French people say they have confidence in schools and teachers.

Help teachers to help pupils

Reforms are needed to get the education system to move forward. More positions must be created, but more direct measures concerning instructional practices are needed. For the SNUipp-FSU, the main primary school trade union, training, team work, and “more teachers than classes” are three major requirements to have the school progress with the teachers. Training is vital, because teachers need to be equipped professionally so that they can teach better.

Primary school teachers give all the lessons in their individual classrooms. In addition to knowledge in their discipline for which professionals need advanced knowledge, training is needed to shed light on the accreditation and transposition of such knowledge so that it can be used in classes with children aged three to 11. This professional dimension is sorely lacking in master’s degree programmes that prepare future teachers for the national competition (in M1) and to join the profession (end of M2). It is moreover necessary to share research findings with teachers throughout their career and to help them to think about and to improve their practices.

Finally, primary school teachers need to work as a team to escape the solitary exercise of the profession. It is useful to have different perspectives on students, their success and difficulties. The presence of “more teachers than classes” is an undeniable factor of educational wealth and inventiveness in the face of difficulties encountered. The sector is teeming with possibilities for teachers to organise the outlines and contents of their work.

All this requires institutional decisions, because volunteering has its limits. The school must be given a new lease on life and teachers must have the tools they need to do their work properly.

By Lydie Buguet, Syndicat national unitaire des instituteurs professeurs des écoles et Pegc(SNUipp-FSU/France)

*Interactive Louis Harris poll: The French and their perception of primary schools, August 2012