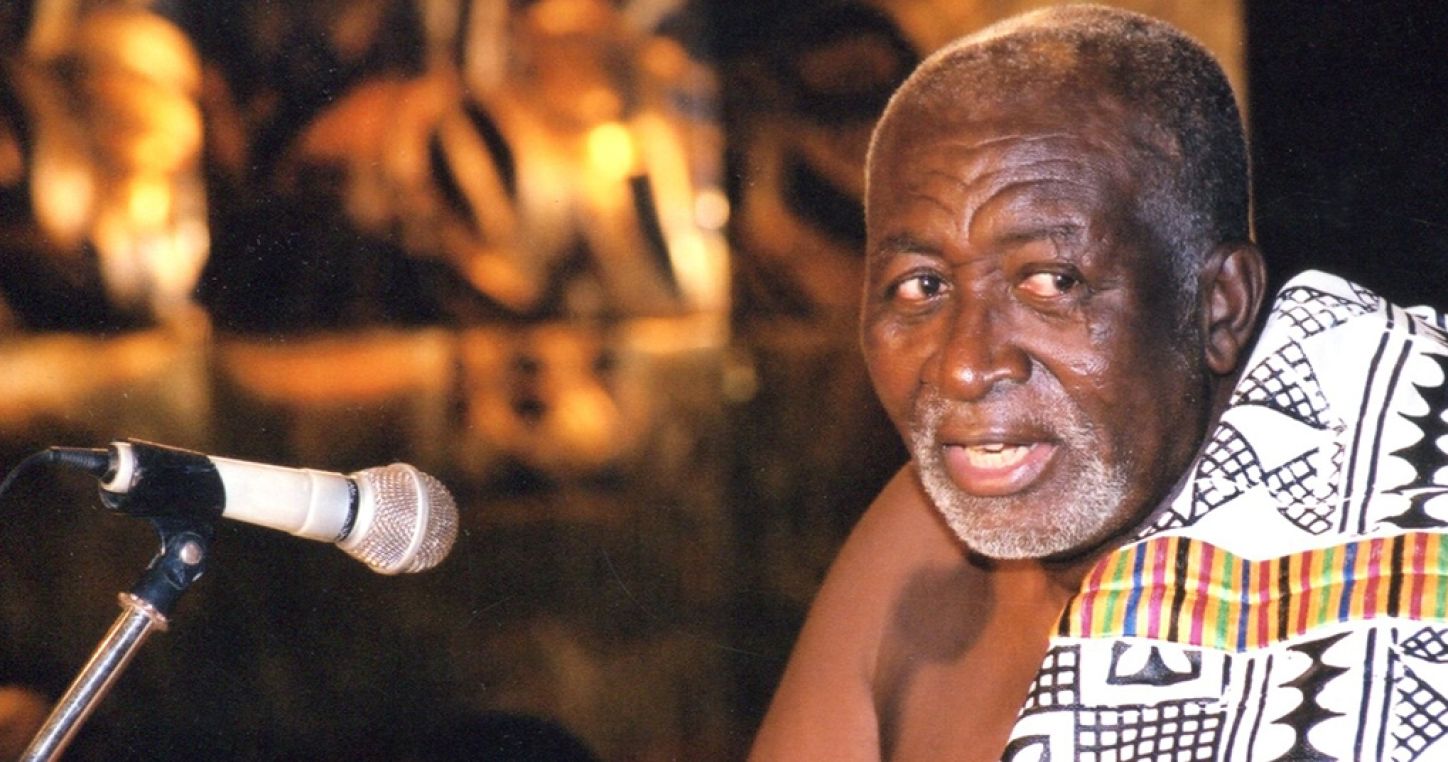

Passing of Tom ‘Father Africa’ Bediako

Education International is sad to learn of the passing of Tom Bediako, an outstanding Ghanaian education trade unionist, who for over 10 years made a considerable contribution to the strengthening of education unions and quality education in Africa as Education International’s Chief Regional Coordinator for the region.”

“It is with great shock and sadness, and a sense of disbelief, that we have learned of the passing of our beloved Tom Bediako,” Education International (EI) General Secretary David Edwards wrote in a letter dated 28 March and sent to Ghana National Association of Teachers (GNAT) General Secretary David Ofori Acheampong

“We join you in remembrance of Tom, who played such an important role in the strengthening of education unions in Africa,” he also stressed, adding that EI will “remember Tom’s endless quest to improve the quality of education and the status of teachers in Africa – not just in terms of access and enrolment rates, but first and foremost in how education can emancipate human beings.”

Edwards recalled that “as EI Chief Regional Coordinator for Africa from the establishment of EI in 1993 to his retirement in October 2003, Tom – ‘Father Africa’ as he was affectionately known to many colleagues - worked tirelessly to ensure that all African teacher unions had at least a fighting chance to develop into recognized social partners by their governments”.

He further describes Bediako as a “dedicated and skillful union activist and colleague but also a close friend and comrade whom we will miss sorely”.

Education International (EI) expresses its most heartfelt condolences to Tom’s relatives, friends and community.

Below Tom Bediako’s interview published in EI’s magazine Worlds of Education 40 in April 2012:

A giant in Ghana education and unionism: Tom Bediako

Ghanaian education leader Tom Bediako has left his footprint on education trade unionism all over Africa, receiving many awards for his work as a teacher and trade unionist for over half a century. Aged 79, Bediako remains sharp and committed. In this interview, he doesn’t look back with nostalgia, but shares his vision for the future of education in his continent. In front of the financial and economic crisis, he underlines, among other issues, the importance of: public investment in education; well-established dialogue mechanisms between trade unions and national authorities; and the importance of building a strong, united trade union movement in education at national and international levels

Invest in educational quality

We have achieved a lot in Africa. Schools have been built all over the continent, even in the smallest, most remote villages. These schools open doors to the world. I consider myself to be the living example of the tremendous importance of making basic education accessible for all in society: rich and poor, in cities and in rural areas. I attended a primary school in my village, and learning encouraged me to keep on learning, to consider studying as a lifestyle. Without that primary school, I would not have been able to go beyond the borders of my village.

We have made progress in access to education. It is, however, sad to note that increased enrolment rates often went hand-in-hand with a decrease in quality. So it is definitely our next challenge to make a leap forward and invest in educational quality. I strongly believe governments should take their responsibility in this respect, ensuring that a public education system is guaranteed and strengthened, and takes into account the student’s mind, heart and body.

Safeguard public education

We should never give up on the broad tasks of education. I see a growing tendency towards a type of education which is solely focusing on testing and examinations. We should not let that happen. A human being in school is so much more than someone who is focusing on results alone. I see that, in such a narrow-minded approach to education, the private schools can flourish well. These schools have no other intention but to prepare the learner for passing exams. These private schools are mushrooming in Ghana and all over Africa because the public authorities did not address the quality issue adequately. It´s time to refocus on quality to safeguard the public system.

No debate on key issues

The teacher’s role has changed dramatically over the past decades in Africa. Often the teacher was the only literate person in the village. In the early days after African countries gained their independence, teachers lived to teach. In Ghana, in Tanzania, Zambia: all over the continent. There was a strong commitment to build the nation. Nowadays, teachers teach to live. I can´t blame them, but they surely work with a different perspective.

It also shows that, these days, teachers and their unions work in a different manner. The unions and the education authorities have established solid bargaining rules and regulations on salaries and working conditions. But look at the professional issues and educational challenges. There is hardly any well-structured debate on the key educational issues. On paper, we have in Ghana the National Education Service Council to discuss these matters. But this consultation mechanism is not being used by educational authorities.

What we need is a well-functioning institutionalised dialogue on educational policies. Too many education unions do not have evidence-based opinions on educational policies. We should work hard on that because, as professionals, we must bring our vast daily teaching experience into the debate.

Unions should look for unity

When I started working as a teacher, there were about 17 educators’ organisations. Today, educators speak with - almost - one voice, with the Ghana National Association of Teachers (GNAT) counting over 160,000 members. And we see this progress towards unity in many countries in Africa, and – obviously – we saw it happen at international level, when the International Federation of Free Teachers' Unions and the World Organisation of the Teaching Profession merged to form Education International (EI).

But I note that unity also sets conditions and has its own obligations to be met. Unions who have achieved unity and have a monopoly position should not be afraid of diversity. When unity becomes a goal in itself, the union runs the risk of reducing its operations to a ritual dance, of having consensus in advance. I see it happen now. There are unions with too little internal open criticism and in-depth analysis. So, the key question is: how do we generate an internal debate to get the best out of members and the trade union?

I have seen the growth towards political independence on my continent. In the past 50 years, all countries moved from colonies to independent nations. However, this has not led to financial and economic independence. We have grown towards a global village in which there are owners and beggars. I see it as a great challenge for Africa to work hard to attain full self-determination. I see that the trade union movement and educators active in this movement should play a role in this.

African identity makes us strong

We are part of a global organisation, but it looks like many unions in Africa have given up on taking their destiny in their own hands. I worked so hard to obtain African teachers’ unity through the All Africa Teachers’ Organisation and the Pan African Teachers’ Centre. I deplore that it did not work out the way I hoped for. We did not succeed in combining membership of the global teaching community with the growth of our own African identity. I regret this deeply because I think that it is our African identity which gives us a reference point and makes us strong.

Personally, I am proud that I have been part of the struggle for freedom and liberation in South Africa and the birth of a great educators’ union, the South African Democratic Teachers’ Union. I was moved that the global educators’ community succeeded in gathering various teacher groupings and organisations into one room and having them adopt a joint agenda on the basis of a common platform.

Looking back, I can see that life has given me unpredictable turns and twists. I became a teacher by accident and to exit poverty. Later on, I trained to become a journalist, a training I did not complete to return to teaching. And, through a series of coincidences, I ended up working for the GNAT. And from there to EI. It has been a long journey from my Ghanaian village to the global village. It is not time for me to go back to my village yet though, as there is still a lot to be done.