“The Movement Against Pension Reform in France: Paradoxes of Teacher Militancy” by Laurent Frajerman.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

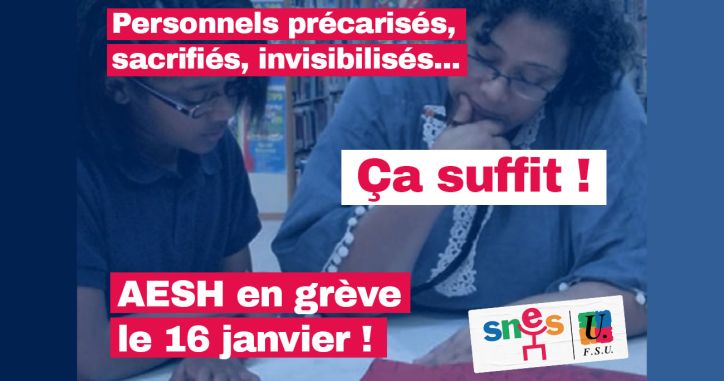

Teachers in France, like in many countries, are simultaneously leading a social movement and facing the prospect of a lowering of their professional status, which would become more acute as a result of the pension reform undertaken by the French government in 2019. But their ‘uber-militancy’ (the use of strikes by teachers being far above the average amongst waged workers) was beginning to wane, in line with the predominant perception in the intellectual and media landscape that striking and trade unionism were in decline.

The failure of the 2003 movement against the previous reforms limited teacher mobilisation: never had teachers fought so powerfully and never had the financial penalties for doing so been so strong. But teachers’ strike culture persisted, basically because the conditions for its emergence – progressive political values, a sense of public service, statutory protection, the strength of trade unionism with almost 25% of teachers unionized , etc. – remained intact. This was demonstrated by the size of the strike of 5 December 2019 and the marches, which put teachers back at the heart of the action. However, the weaker follow-up to this action also shows that there are still barriers to strong, lasting mobilisation. An analysis of these events is useful in the context of the suspension of the reform when COVID-19 appeared.

Teachers’ willingness to strike confirmed

It was the most successful strike since 2003. Of course, the official figures did not reflect the reality on the street and were entirely lacking in transparency: the minister counted people who could not strike as non-strikers. The underestimated figures do, however, provide a brief overview of developments.

Approximately 65% of teachers took part in this movement. The December 5th 2019 mobilization was far larger than usual and close to the maximum participation rate: 85% of teachers have gone on strike at least once during their career[1]. While 30% of teachers regularly go on strike, 40% only exercise their right to do sooccasionally, and 15% of teachers go on strike only in exceptional circumstances. This smaller group are more often on the political right and socialise in circles in which this form of action is a foreign concept (private schools, tradespeople and private sector workers etc.). The success of 5 December was the result of a combination of regular and occasional strikers. It is not always obvious that these groups come together: in 2015, only half the teachers opposed to secondary school reform mobilised against it. Succeeding in gaining majority support for a strike involves convincing the intermediate group, which is less sensitive to trade union unity than regular strikers. The particular feature of this movement was that it started very strongly, with a strike announced more than two months in advance, which then became reduced to the regular strikers, although no-one was unaware that prolonged action was required considering what was at stake.

The role of trade union action

A year after the emergence in the media of a non-union protest group on Facebook – known as the “stylos rouges” or “red pens” – the movement marked the great comeback of teacher trade unionism, even though it is fragmented into more than seven organisations, each with its own history and identity. The two main unions (the FSU and UNSA) are the heirs to what was until 1992 the main organisation: the Fédération de l’Education Nationale (National Education Federation). Each trade union confederation also wanted to establish itself in this strategic sector of waged workers. At key moments, these forces regrouped almost systematically along a fault line between the reformers (UNSA and CFDT, together accounting for 24% of votes in 2018) and militants (the FSU, 42%, occupying a central position, and three activist unions, above all the FO, which, with the CGT and SUD, has 22% of the votes). The FSU is the majority organisation, both in terms of votes and activists.

The positioning of these blocks with regard to action depends on their strategy (the reformers prefer negotiation and the occasional expression of discontent) as well as the inclination of their supporters. The sphere of influence of each trade union consists of its members and sympathisers and the diagram below shows that those associated with the radical unions participate frequently (33%) or regularly (30%) in social movements. Pushing to step up action towards an indefinite strike is, therefore, coherent with their bases (talking is more highly valued by reformist unions, whose activists are less militant). Teachers who have never been members of trade unions and who are not openly close to any organisation rarely (60%) or occasionally (23%) take action. This confirms the central role played by trade unionism in constructing and maintaining teachers’ willingness to strike. Each bloc has played its part: the combative organisations have led the movement with the confederated unions (CGT, FSU, SUD and FO), while the reformists have supported certain strike days (5 December for the UNSA but not the CFDT, which led to internal debates, and 17 December for both).

Weekly demonstrations or indefinite strike?

The most militant professions in the country are in the national education and transport sectors. The government rather presumptuously took on both sectors at the same time with particularly regressive measures. But the convergence between strikers was accompanied by a lack of synchronisation. Traditionally, in fact, teachers prefer short-term action. First and foremost, their strikes are a rallying call to public opinion, not an attempt to stop production. Teacher mobilisations alternate between months of a show of strength and awareness-raising actions particularly aimed at the media and the public. By contrast, transport employees carry out indefinite strikes coupled with General Assemblies.

As in 2003, radical militants, either members of the FSU or supported by the militant confederations (CGT, FO and SUD), are trying to reproduce this more active model among teachers. Many militant teachers are being mobilised for long periods, often several days. Indefinite strikes have allowed them to mobilise citizens and build momentum by occupying local and media spaces (demonstrations in shopping centres, occupation of institutions, torchlight marches, etc.). However, the general strike failed after December 5th. Moreover, the absence of weekly shows of strength, replaced in mid-January by three consecutive days of mobilisation including two strikes, was disastrous. We can, therefore, draw the conclusion that teacher mobilisation has stalled, particularly among occasional strikers who cannot see themselves in the kind of workers’ struggle they consider to be too radical. This debate could not be resolved democratically because the General Assemblies included, above all, the most highly motivated teachers and there were no forums on the internet.

Conclusion

This movement was, therefore, a deeply ambivalent one: is December 5th, 2019 going to remain an isolated rumble of thunder? Can teachers’ unions repeat it with careful united preparation? It is not clear that they can achieve a lasting mobilisation of occasional strikers: those who refuse to commit themselves to strikes barely participate any more in alternative actions (Saturday demonstrations, for example). However, while the fatalist discourse legitimises their lack of investment, it also demonstrates a search for direction. French teachers regret the struggle’s current lack of effectiveness, they do not reject the struggle in itself. The current sequence of events, therefore, brings hope and is a source of reflection for teacher trade unionism provided it reconnects with its own culture.

--

[1] Militens poll, 3,300 teachers, FSU, CERAPS University of Lille, DEPP National Ministry of Education.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.