On Edtech, the public good, and democracy

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought death and despair. However, it has also sharpened our vision. We have seen dangers more clearly and trends that were threatening the health of our societies. In some areas, like inequality, it is apparent to everybody. In others, however, risky developments are partially hidden. These include the growing influence of the private sector and advanced, including intrusive technologies on education, but also on larger society.

In the last year, Education International has commissioned and published research on the intersecting worlds of private sector influence on education and the deployment of distance teaching and learning technologies by Ben Williamson and Anna Hogan. They are entitled Commercialisation and privatisation in/of education in the context of COVID-19 and Pandemic Privatisation in Higher Education: Edtech & University Reform. Read More

Both studies show how the pandemic and the dependence on distance learning expanded the role of private companies in education from the Googles of this world to start-ups. However, their extensive research had its limits. Much information is obscure due to intellectual property protections or for other competitive reasons.

Many companies made new technologies available for free or at very reasonable prices. Such “generosity” in the form of “free samples” will pay off in the corporate bottom line in the long run.

Public-Private-Partnership (PPP)

Much of the focus of the EI Global Response campaign has been on private, for-profit schools, often part of multi-national companies like Bridge International Academies. They see their part of the “education market” as the operation of schools financed by public authorities. Although they have made inroads in some countries, their presence is visible and, with research and persistence, their weaknesses can be exposed. Although that threat to public education must continue to be fought, there are additional dangers.

The massive influx of private, ed-tech companies into public education systems is a different market development approach. It is less visible than privatisation of schools, but, in some ways, more insidious. It is private influence, often by global companies, into the content of and approach to education.

In some ways, it is much more difficult to deal with PPPs than with privatisation. If adapting education to the impact of COVID-19 accelerates the long-term integration of ed-tech companies into the infrastructure of education, that may have a lasting impact. Separating the “good” from the “bad” may be as challenging as unscrambling an egg.

Any fundamental change in teaching and learning should be the result of conscious decisions based on values and pedagogy. It should not just happen. Technology needs to be a tool of education and not the other way around.

Public-Private-Democracy

Schools and other education institutions have a long experience with business. If a school is to be built or modified, they hire construction companies. If they buy food for the school cafeteria, they deal with companies that provide food. They do not, in most cases, print textbooks themselves even in those school systems that still write or approve them.

Traditionally, business has profited by providing something tangible and temporary. For the tech giants, their services go to the core of education even if they make their money less from services than from access to and use of data. In the traditional school-business relationships, there was a line between private gain and the public good. With the new Capitalists, that line is becoming blurred.

There is another problem with PPPs, despite their popularity with politicians. The problem goes beyond the fact that they often turn out to be neither economical nor effective. The danger is more fundamental. If policy decisions are being made by a PPP, is there such a thing as a public-private-democracy?

PPPs have the built-in problem that both parts of the partnership are making decisions, but only one part has a public mandate and is subject to democratic rules and practices, including transparency. So, our democracies risk becoming half-democracies.

A Trend or a Tsunami?

Following the pandemic, new technology is not going to disappear from schools. However, like so many things in the post-COVID world, it is urgent to cull through experience, evaluate impact and measure positive and negative effects. The use of technology should be deliberate choices and should not just move forward with no questions asked.

Those choices should be based on transparency and public information. That includes on such issues as the role of artificial intelligence, algorithms, and the use of data. It also needs to complement, not undermine education and be consistent with its mission.

A trend boosted by the pandemic does not have to conquer all. There is not an inevitable dominance of machines over humans.

There are many lessons from the pandemic. They include:

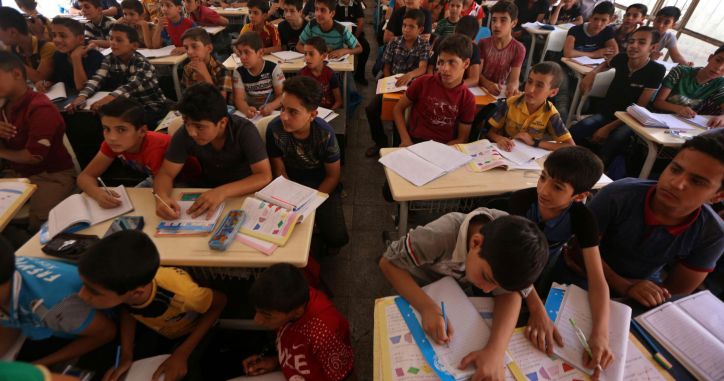

- People are social animals. They learn from each other and benefit from relationships in schools.

- With rare exceptions, isolation holds back learning, especially for those who do not have an enabling learning environment at home and in their neighbourhoods.

- Robotised instruction can never substitute for the role and judgement of professional teachers.

- Education needs to be part of local communities and cultures. It should not be the prerogative or the property of private, often global, interests.

- The crisis of democracy and the fuelling of hatred and intolerance has been nourished by some of these same companies. Civic education needs to be able to counter disinformation and mass deception. It should not risk becoming part of such networks.

- Schools need to spawn critical thinking and inspire young people to protect the planet and fight for social justice. Both are hands-on, in-person processes.

- Public policy discussions are underway not only on the concentration of the industry, but also on its role and associated dangers. Measures are being considered to regulate them and set limits to their influence, which will affect education.

- The use of artificial intelligence and other means is having an impact on the way that we work and the future of work. EI is examining those issues. Anything that damages the profession, and the well-being of teachers will damage education.

This does not mean that a qualified teacher must be able to design algorithms. However, it is important to be aware of the dangers.

The context, restraints, process and policy framework for technologies are critical. They are everybody’s business, inside and outside the education community. Choices made must be of clear benefit to students and teachers. They should conform to the purpose and mission of education.

This transition period after the pandemic, when so much is at stake, makes it even more urgent that educators through their trade unions are at the table when policy is discussed, developed, and decided.

Educators and their organisations are not only fighting for quality education but are also on the frontlines of the fight for freedom and democracy. We should recognise that our efforts, in the classroom and beyond, are a crucial part of that struggle.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.