Privatisation is a big threat to quality of learning in Kenya

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

By Wilson Sossion

General Secretary KNUT

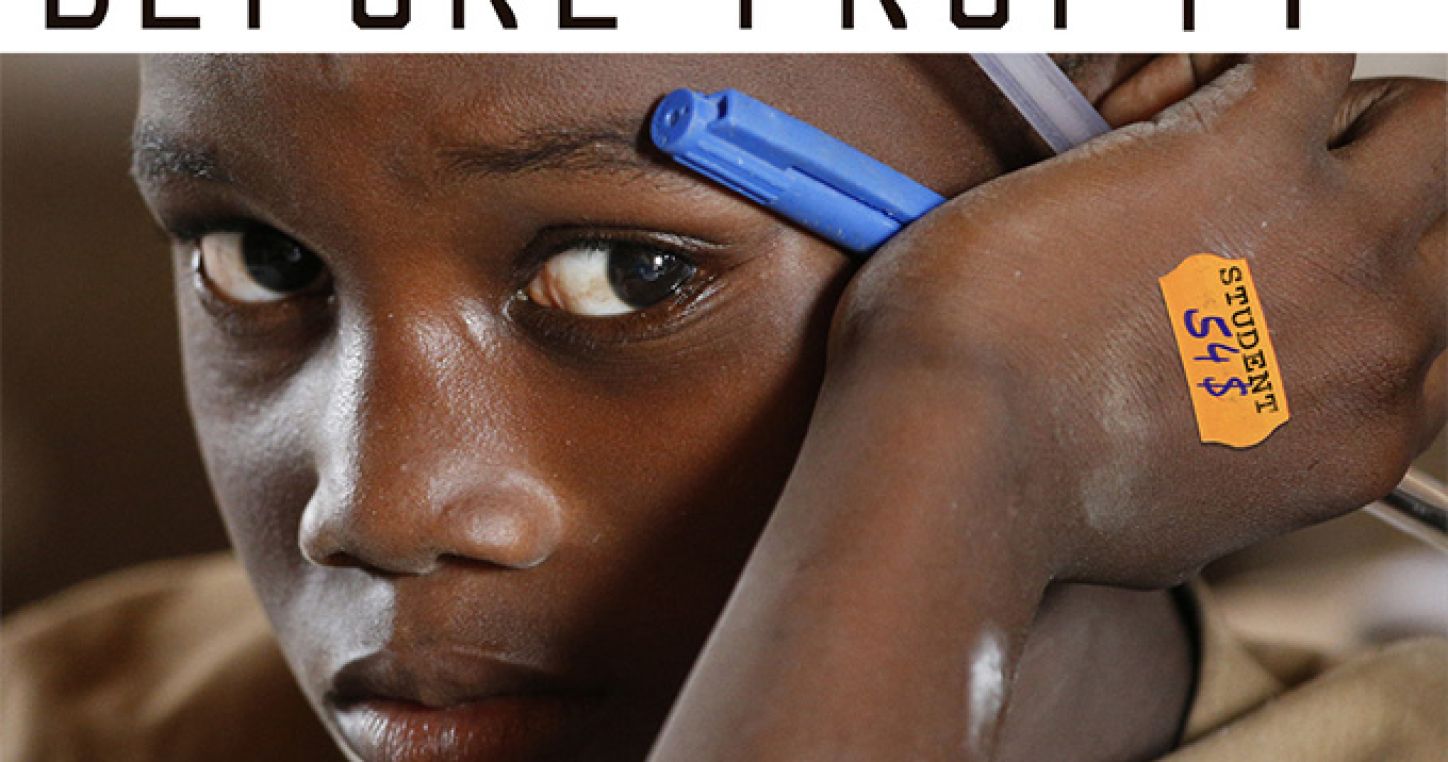

Debate has been raging in the past decade over deteriorating standards of public education and how to fix it.

In view of the many challenges that confront public education systems, privatisation, in its different guises, has become attractive to policy and decision-makers.

Discussions have shifted from education as a public good and the platform for this debate has been staged by what has become known as the corporate education reform movement.

Complex alliances and power blocs have formed across a number of countries that have increasing influence in education policy-making.

From the so-called “low cost schools” to shadow schools, to vouchers and for-profit charters, this movement is simply profiteering disguised as philanthropy.

Assault to public education

Privatisation is, indeed, an assault on the very essence of public education and education as a human right.

It is falsely argued that privatisation provides choices to parents and guardians, makes schools more responsive, and produces greater cost efficiencies and even better quality education.

This approach is derived from the idea that the State should have little to do with the delivery of education and other services, which are best left to market forces.

We argue that the proposed “market solution” to our education crisis, even with State regulation, is less a case of a pragmatic attempt at resolving the problem than a case of ideological wishful thinking.

Privatisation, which leads to commercialisation, does not solve the problems in education; rather it makes them worse whether in Kenya or elsewhere in the world.

In reality, the privatisation of education is the pursuit of a global ideological agenda rationalised on the failure of governments, Jubilee government included, to supply good quality public education to the majority of its citizenry.

This ideological agenda is uncaring about education as a public good and a catalyst for social cohesion and equity.

Reducing education to a business distorts the purpose of good quality public education.

Jubilee Administration

It is not for nothing that many communities in Kenya have complained that the Jubilee administration is failing to deliver quality public education.

Abandoning these challenges for the false promise of privatisation is to discard the rights enshrined in the Constitution (2010), Education Act (2013), TSC Act (2012), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other relevant international conventions and treaties protecting education as a human right.

Public education has developed over more than a century to become a core aspect of the work of governments, especially because it is very much a part of their democratic mandate in providing a basic human right to all members of the society.

Nowhere is there an example of a country with high educational outcomes where the provision of basic education has been in private hands.

We are not opposed to low-cost private schools operating in the country.

They were established in response to the many challenges faced by Kenya’s public primary school system, including teacher absenteeism, low motivation, crowded classrooms and run down facilities.

What we are opposed to is the high fee charged, low quality education offered, pupils being handled by untrained teachers and worse, some schools using curriculum not approved by the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development as required by the law.

We are aware the World Bank, Microsoft founder Bill Gates, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, International Finance Corporation, Commonwealth Development Corporation, Omidyar Network, among other high profile investors have been supporting these institutions.

They should continue doing this, but on condition that they operate within the law and comply with minimum standards.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.