U.S. and International Feedback Loops on the Privatization of Education

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

By Frank Adamson, Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education (SCOPE)

On July 5th, 2017, the Education Minister of Liberia, George Werner, gave a keynote speech in Washington D.C. that outlined the role of charter schools in the developing world. [1] It is worth unpacking the empirical and geographic layers of his address to understand its ramifications within the context of global education reform.

The message of this event – that charter schools are good for the developing world – attempts to connect the “policy-borrowing” loop in which experiments in the global north (U.S. charter schools and U.K. academies) are exported to the global south, with the profit accruing back to companies and international organizations in the global north, who then support the “free enterprise” narratives used by AEI and similar institutes. [2]

At a root level, advocates of market-based education reform have created an international feedback loop based on insufficient evidentiary support while proponents of the right to free public education have a strong evidence and legal base, but have not developed a strong feedback loop between the U.S. and international contexts.

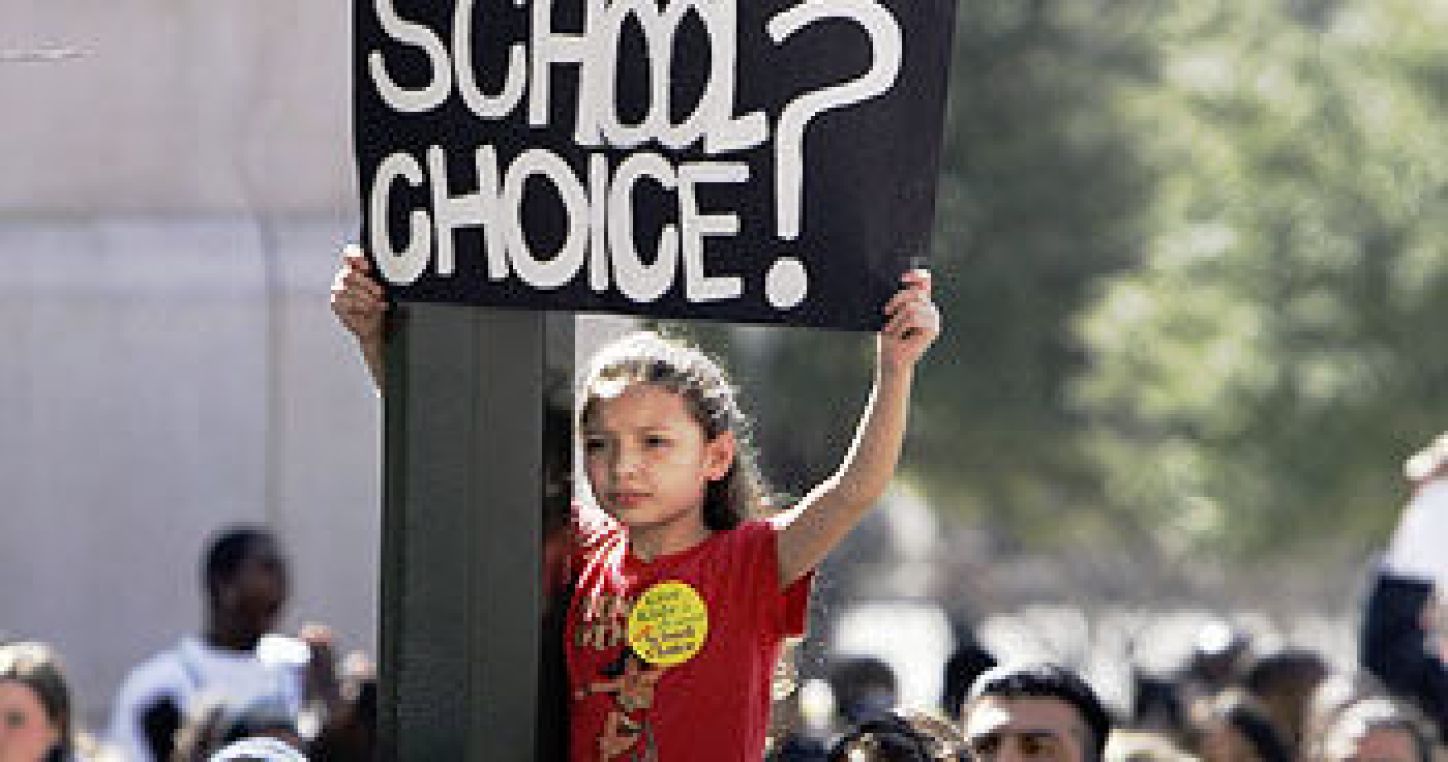

At the level of evidence, the policy proposals of charter schools specifically, and “school choice,” writ large, lack clear positive research results. New Orleans is often cited as a successful charter school model (even by Minister Werner himself), but research by this author and others has identified an increase in the stratification of education opportunity when systems shift to charter schools. [3]

On the larger issue of school choice, Carnoy outlines a host of U.S. and international studies that show, at best, a mix of positive and negative impacts of school choice models. [4] This evidence certainly does not demonstrate the high levels of positive effects that would merit worldwide expansion of school choice via vouchers, charter schools, markets, and low-fee private schools.

Nevertheless, such policies proliferate. The proponents of education reform, in the form of a host of entities such as corporations and bilateral and multilateral banks and organizations all benefit from exporting market-based education reform.

However, the response to this set of market-based approaches remains geographically disconnected. Two recent reports, one U.S. focused and one international in scope, offer strategies for navigating the privatization of education. These two reports exist in siloes without a strong connection between the contexts.

The U.S. report details the deleterious effects of charter schools in the U.S. and proposes a set of recommendations including a moratorium on charter schools. The international report also details the impact of public-private partnerships (or PPP’s – the international version of charter schools), as well as low-fee private schools, vouchers, etc. This report also offers a set of strategies for limiting the privatization of education and helping governments better deliver on the right to education.

The juxtaposition of these different feedback loops can be explained somewhat by ideology, political, and economic power. The AEI-IFC-Liberia connection proposes “free market” solutions from the seats of government supported by wealthy organizations. [5] Global civil society organizations have more disparate drivers and constraints, but when very similar issues emerge as they do in this case, proponents of the right to free public education would do well to create their own transnational axis of communication and movement building.

In particular, the U.S. both invents and exports many market-based education strategies beginning as far back as vouchers in Chile, so understanding its context and the strategies and responses of its citizens is important for the global community.

The theory of “policy borrowing” illustrates how governments and other entities can refer to policies in different countries and contexts to gain legitimacy for their own political goals. The education reform movement continues to develop this transnational feedback loop, as illustrated in the Werner address, while proponents of the right to free public education have yet to create a fully functional set of feedback loops. While such an approach may not be necessary, this strategy seems to be working for the proponents of market-based education reform.

Dr. Frank Adamson is a Senior Policy and Research Analyst at the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education (SCOPE). The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and may not reflect the views of this organization.

[1] http://www.aei.org/events/charter-schools-in-the-developing-world-a-keynote-address-by-liberian-education-minister-george-k-werner/

[2] Gita Steiner-Khamsi explains how transnational “policy-borrowing” operates in Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2016). New directions in policy borrowing research. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17(3), 381-390. For an analysis of the Liberian experiment, see: http://ncspe.tc.columbia.edu/center-news/working-paper-liberias-experiment/

[3] https://www.frontpageafricaonline.com/index.php/politics/283-liberia-s-education-predicament-profiting-off-poor-or-answer-to-a-messy-system; https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/publications/pubs/1374

[4] http://www.epi.org/publication/school-vouchers-are-not-a-proven-strategy-for-improving-student-achievement/

[5] The IFC is the International Finance Corporation (the private arm of the World Bank), which both hosts a biennial conference on the privatization of education and participated in the panel following Werner’s speech at AEI. It represents another node in this transnational feedback loop, discussed in more detail by researchers such as Stephen Ball and Toni Verger.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.