An attempt at the first ‘Davos of Education’: Dissonances in the OECD-Forum for World Education on The Future of Education

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

By Camilla Addey and Antoni Verger, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain

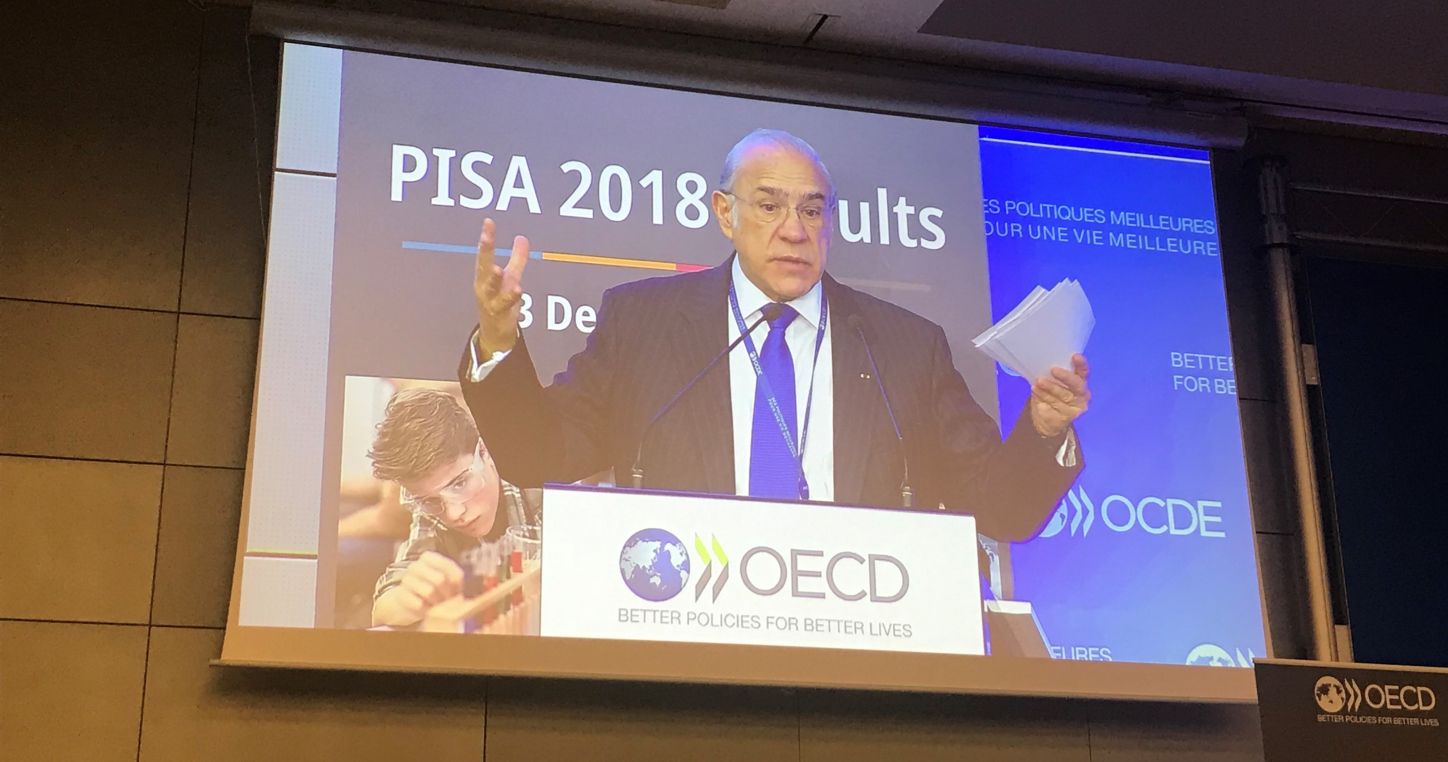

This year’s PISA 2018 data launch on 3rd December 2019 was no normal launch. Angel Gurría, the Secretary General of the OECD, released the league tables, focusing his analysis on top performers (which included, as is becoming usual, a group of Chinese cities and East Asian countries). Andreas Schleicher was next to talk. His talk highlighted how society and the skills it requires have become more complex since the start of PISA, in contrast with an almost flat line of average PISA-skill growth worldwide since 2000. His slides focused mainly on the new OECD buzzword ‘the growth mindset’, student attitudes (described as skills that robots cannot learn) and the importance of teacher enthusiasm. Bar the new buzzword, nothing new and not many policy implications to be drawn [1]. So, should one say that PISA’s value seems to be fading? How can the OECD keep attracting participants and advocates?

Maybe the partnership with the Forum of World Education was such an opportunity. Indeed, the PISA 2018 data launch was followed by the first Forum of World Education, a two-day event on ‘The Future of Education: Where do we go from here?’, hosted by the OECD in Paris.

Intended as the ‘Davos of education’, the Forum is a newly established non-profit set up by Cheng Davis, a special advisor to top US universities who is unknown to many, but very well connected. ‘Our education policy makers should spend more time with business leaders’, stated Cheng Davis, in her opening FWE speech. The FWE claims it is a non-political non-profit. Based in the USA, it is run by a very influential Steering Committee and driven by the belief that education needs to be transformed to better prepare youth for employment. Its academic committee is led by Stanford University professor in economics of education, Eric Hanushek. About 300 people – global business leaders, investors, global young leaders, education entrepreneurs, celebrities, policy makers (mainly former ministers of education) from top performing PISA countries and a handful of academics were invited to attend the first Forum. The stated aim of the event was to bring together global young leaders (very successful young entrepreneurs - though their selection was never explained) and influential global business men and women to share ideas on how to transform education and commit to the Forum’s Paris Declaration (which was read out in haste at the end of the event).

Rather than starting out from what world we want and how education can help to create that world, the basic assumption was that education has to modernize and respond better to the changing needs of the economy and the digital world where we live. Many global business leaders, who employ dozens of thousands of people all around the world, including billionaires like Jack Ma (Founding Chairman of Alibaba) and Sir Richard Branson (Founder of Virgin Group) highlighted their poor and frustrating schooling experience when they were kids, and how their philanthropic efforts aim to give young people the opportunities they did not get.

Four issues stood out during the two days. Firstly, there was not a clear story line in the event, with a dissonance between, on the one hand, an approach aligned with PISA data, evidence-based policy, global education expertise and, on the other, what could be described as anecdotal, personal stories of global business leaders drawing on their school and business experience to suggest ways forward to transform education for the future. The divergent approaches to accountability stood out between those arguing for softer forms of accountability, more professional autonomy and trust in teachers (including former education ministers and high ranks from Singapore, Finland and New Zealand), and those, such as Eric Hanushek, claiming that the solution to ensure quality and equity in education is to fire the 10 per cent of lowest performing teachers. Recurrent solutions seemed to be skills for employment, personalized and online learning, and good quality teachers who inspire, change lives and consider themselves nation-builders.

Secondly, the discourses about education in the panels and keynotes of the Forum emphasized the importance of emotional skills, innovation and co-creation; and even the need of a systemic redesign of education through which to surpass schools as the main educational institution. However, these grandiloquent ambitions were often accompanied by a narrow understanding of the purpose of education aimed mainly at training flexible, highly skilled workers. ‘ Universities should be like a company – they should analyse what product is needed and then produce it so that we do not have to retrain them’, stated the Varnee Chearavanont Ross, the Founder of Concordian International School.

Thirdly, the Forum seemed to convey a geopolitical shift: not only did PISA’s 2018 results show five of the top ten PISA educational systems as Asian, but Asian (mainly Chinese) speakers and participants played a prominent role in the Forum. Interestingly, both Andreas Schleicher and Jack Ma argued that it is time that Western societies learn more about Eastern cultures, religions, philosophies (the concept of Confucianism emerged several times), and that Asian students who study abroad seek to share their cultures widely rather than just learn about the West to transform the East.

Finally, Andreas Schleicher’s wrapping up statement insisted on education no longer being about reading literacy, Math and science but about global competencies, attitudes, and values. He praised the OECD’s Study on Social and Emotional Skills as its most innovative educational endeavor, recommending global business leaders go home to lobby their governments to participate in this new international large-scale assessment. Interestingly, the only time Andreas Schleicher mentioned PISA in his final closing statement was to say that PISA has to change in the way it assesses competences, even though stakeholders are resisting change in the name of longitudinal data: ‘ We are sacrificing relevance for reliability’ he concluded.

Drawing on global business leaders and young global leaders sets a new profile for an emerging group of OECD’s expert advisors and partners, with money and fame as their credentials. As scholars, we observed the event, seeking to understand what agenda the OECD is furthering through this partnership. Is it that the OECD is simply seeking to widen its conversation on education to include new partners? Is the OECD seeking to tip the world epicenter of educational debates towards East Asia? After the PISA fatigue, which became more obvious this year, is the OECD seeking new audiences for PISA data and OECD policy advice? Or is it rather seeking new advocates and networks for new OECD programmes in a post-PISA era? The answers to these questions are not written yet, it may be that they are in the making as the OECD seeks to hold the position it has come to hold in education. Some partial answers may be found in the next PISA round, or at the second FWE, which will be held in Washington DC in 2020.

[1] And we will need to wait to know what the policy recommendations are deriving from PISA 2018, since the volume focusing on policy, volume number 5, will not be released until June 2020.

Photos are from the authors.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.