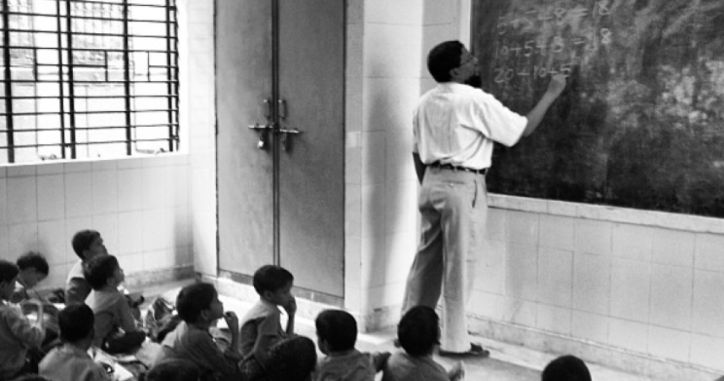

Teachers as democracy workers

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

The work of teachers is something of a contradiction. Governments, policy-makers, educators and parents are often quick to point out the importance of education for young people – and that necessarily highlights the value of teachers. Yet at the same time, in many countries around the world, the profession of teaching is one that is often derided.

Sometimes, it is called ‘nothing more than baby-sitting’. Other critics contend that it’s easy, too well-paid, and that the benefits include long holidays and no accountability. Sometimes, these attacks get personal: teachers themselves are accused of being less than intelligent, or apathetic, or failures in every other role: as the saying goes, ‘those who can, do, and those who can’t, teach.’

All of this occurs while teachers and education systems are being called upon to do more and more to address concerns about society.

Teachers in many countries now have to do much more than teach the curriculum. They must educate young people about topics as diverse as consent and privacy, digital citizenship, and road safety. Increasingly, teachers are expected to challenge and confront mis- and disinformation in their classrooms. In some cases, teachers are required to challenge racism and prejudice – and all the while, the profession itself is often belittled and criticized as being ‘too woke or ‘too liberal’ or ‘too ineffective’.

These attacks on education and teachers illustrate a vitally important, but often overlooked, point. Teachers, and the education they provide, are essential for the functioning of democratic nations. That is why there are sustained attacks on educators in countries where democracy is at risk. That is why education continues to be a central point of argument and policy debate in many different countries.

“Teachers have the capacity and the responsibility to nurture and protect those sensibilities, values and institutions that are vital to the working of any nation that lays claim to be a functioning democracy.”

Recently, in Australia, the concept of what should be taught in History – and what that meant for Australians, was the focus of ongoing and often quite heated arguments between teachers, historians, political commentators and the education minister. It is why, in countries like the USA, there are ongoing arguments about what books should be available in school libraries, and what young people should be taught about racial injustice.

This is taking place because teachers are essential in the development of young peoples’ understandings of what it is to live in a democratic society. The education system, and therefore the teachers who work in that system, have a direct connection with the vast majority of young people in any given country. What they teach them about democracy and civics and citizenship will be something that will stay with those young people as they grow up and become more involved in their local and national communities.

It is not an exaggeration to say that teachers are democracy workers; that is, they have the capacity and the responsibility to nurture and protect those sensibilities, values and institutions that are vital to the working of any nation that lays claim to be a functioning democracy.

But this is easier said than done. Scholars and teachers, from John Dewey to bell hooks and beyond, have all noted the importance of teachers in this respect. Indeed, many countries’ statements about the value and importance of education either explicitly or implicitly recognize the role played by teachers in this arena. However, the challenge lies in overcoming those voices that criticize the profession and carving out time and space to match the principle with the practice.

In a decade of studying civics and citizenship teachers, I’ve identified three ways that teachers might do this.

Firstly, teachers should use current and recent events as part of their practice in the classroom. In Australia, there is often a focus on the study of civics and citizenship as history; that is, what has happened in the past, such as Federation. But this negates the fact that young people in classrooms are capable of being active in the issues that are affecting them and their communities today – and likely much more interested in these, too. To remedy this, teachers should teach civics and citizenship as something that is happening now and emphasize the role that young people have to play in that area.

Secondly, teachers can model their own active citizenship as an example to young people. Teachers might be active in community groups, sporting clubs, education unions and professional associations. All of these can serve as ways to demonstrate to young people the value and importance of being an active and informed member of their communities.

Of course, I am not advocating for indoctrination into a particular point of view – and that underlines my third recommendation. Teachers can also model ways to resist anti-democratic action. As the world confronts what appears to be a rise in extremism, often at the expense of ideas like multiculturalism and inclusivity, teachers can and should showcase to students what global citizenship and democracy looks like, in the way they promote inclusivity, manage disagreement, and build consensus in their own classrooms. More importantly, teachers can educate young people about the dangers of these approaches, too.

At first glance, this looks like I am adding more to teachers’ already overwhelming workloads. I’m not; instead, I am suggesting that the ideas and principles I document above should be fundamental to the rest of the work that teachers undertake, rather than often overlooked ideas as they currently are.

These are the very foundations upon which education should rest; if we’re not teaching young people to be active and informed members of their community, able to work towards a more just and equitable society, then I question the value of our education system as a whole.

Editor’s note: This article is a summary of Keith’s chapter in the book he co-edited with Steven Kolber Empowering Teachers and Democratising Schooling: Australian Perspectives.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.