Quality public schools, empowered teachers and a student centered approach are key to eliminating child labour

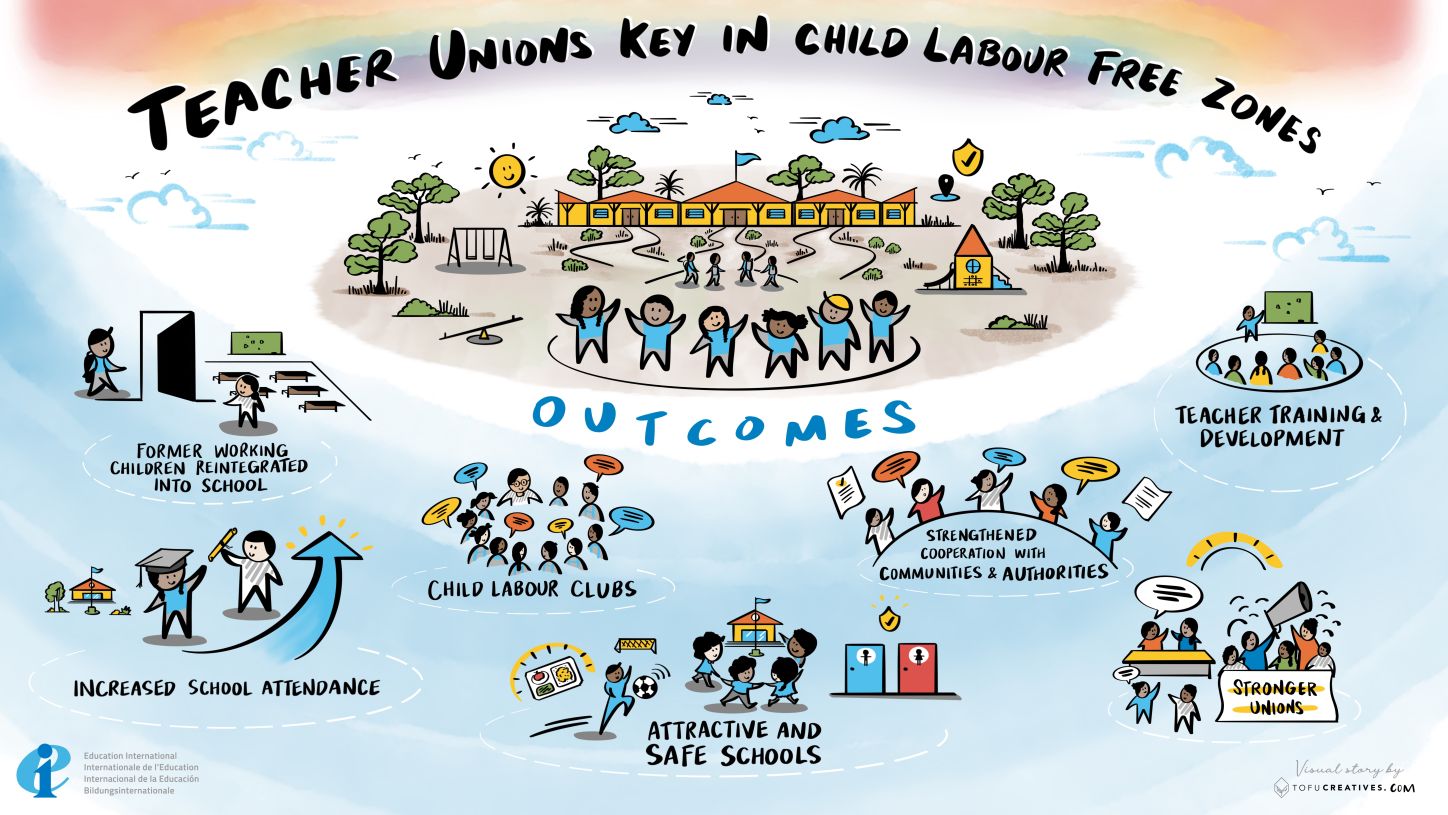

Projects to address child labour carried out by Education International affiliates in 15 countries (1) have enabled more than 8,000 former child workers to return to school over the past nine years. Awareness-raising campaigns, visits to parents by teachers and local authorities, and the adoption of local by-laws banning child labour are among the keys to the development of child labour-free zones.

Education International believes that school communities provide the best environment for children. As shown by the projects put in place by our affiliates around the world, a quality public school, with well supported and empowered teachers, and a student-centered approach is the key to addressing child labour. EI continues to call on governments to support teachers and their unions as they advocate for children's rights by investing in public education.

Getting working children back to school, however, is only one of the steps in the fight to eradicate child labour. Once in school, the child must stay there. Safe and attractive schools are needed to prevent further drop-outs. All the trade unions involved in these projects are therefore strengthening social dialogue at local and national level to improve teaching conditions.

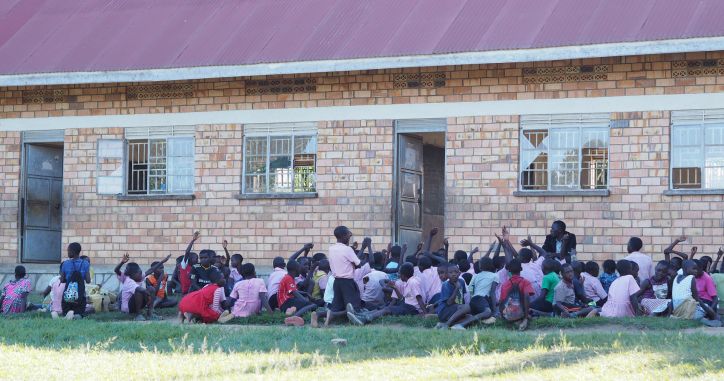

In Malawi, for example, 1,971 children were withdrawn from work between 2021 and 2023 to join 15 schools in Chigudu (Dowa district), where the TUM and PSEUM trade unions have developed a child labour-free zone project. As well as raising awareness of the risks associated with child labour, the unions have trained Chigudu's school management committees in advocacy and resource mobilisation techniques. As a result, they secured the deployment of 53 new teachers in the project area from the Ministry of Education to help alleviate the teacher shortage. These committees have also mobilised funds at local level to renovate classrooms, build toilets and houses for teachers.

In the remote village of Matanda, the union project supported by local chiefs brought 242 former child workers back to school in one year, but the school had only two teachers because there were no drinking water wells. The teachers sent to Matanda only stayed for a few days before returning to the city. As a result, more than half the children brought back to school quickly dropped out. Union lobbying of the authorities resulted in the construction of a well, enabling the return of teachers and pupils who had dropped out. Currently there are eight teachers in the Matanda school.

Unions provide training in better teaching methods

EI unions involved in projects to combat child labour also train their members in child-centred pedagogy and active learning techniques. They are working with experts from the Ministries of Education to ensure that rote learning methods and the use of corporal punishment are abandoned in favour of a child development pedagogy that encourages participation and the use of positive disciplinary methods.

‘In our school, we now use error-based teaching, which we knew little about before the union training,’ explained Abdelihahe Eloudrighi, a teacher trained by the Moroccan union SNE-FDT in the province of Taounate. ‘Before, if a pupil made a mistake, they were punished, which meant that the children were afraid to speak up. Now, we help children to accept their mistakes and correct them. We also take more account of the age and social level of the children. We have seen a big change: children are no longer shy, and both boys and girls feel comfortable expressing themselves at school. This is also reflected in a reduction in absenteeism: children know that they will not be punished if they have not done their homework, because we will take into account their family situation, for example, whereas before they would not have dared to come into school, and repeated absences lead to children dropping out and working’.

Artistic and sporting activities to attract pupils

In Malawi and Uganda, EI affiliates involved in the projects are training teachers in the ILO SCREAM programme, a series of teaching modules designed to promote respect for children's rights. Pilirani Kamaliza, project coordinator for the TUM and PSEUM affiliates: ‘Children learn about their rights and how child labour puts them at risk. It is a way of giving them a sense of responsibility so that they do not drop out of school. Some combine school and work, sharing what they learn in SCREAM with children who work full time, which can convince the latter to return to school. SCREAM is also an interactive methodology, using music, games and drawing to teach children's rights. These activities make the school environment more attractive, which helps to retain pupils.’

Artistic activities are also central to the activities carried out by the anti-child labour clubs set up in most of the schools included in EI affiliates' projects. Pupil members of these clubs are supervised by a teacher and develop street theatre, songs and poems to raise awareness of children's rights and the importance of education. As with SCREAM, these artistic activities make school more attractive to children, particularly former child workers. ‘We have been able to bring 63 child workers back to our school since 2021 (32 boys and 31 girls),’ explained James Siyamachira, headmaster of Gatu primary school in Zimbabwe (Muzarabani district). ‘We offer them the chance to take part in club activities, to help them reintegrate and to increase their interest in school’.

In the same Muzarabani district targeted by the ZIMTA and PTUZ trade union project, the sporting activities made possible by the project have also attracted many children to the classroom. ‘We bought footballs, volleyballs and netballs thanks to the project's support,’ explained Edmore Namutena, head teacher at Clearmorning primary school. ‘This is one of the reasons why 117 children (64 boys, 53 girls) have returned to our school instead of working during the day. One of them is so good at football that he was spotted by a private secondary school in the district, which offered him a scholarship to continue his studies when he graduated from primary school’.

Getting a birth certificate

Pupils sometimes drop out of school because they do not have a birth certificate, preventing them from sitting the exams leading to a diploma. This is often the case with children attending primary school: so as not to deprive them of schooling, the school authorities accept their enrolment and allow them to progress from year to year, but the pupils will not be able to sit the exams leading to a Primary School Completion Certificate if they do not have a birth certificate. EI affiliates are stepping in to remedy these shortcomings. In Senegal, for example, in the commune of Bambilor, the EI affiliates' project has set up an extremely active Association of Pupils’ Mothers (AME – Association des mères d’élèves), which works with school teachers to identify all children without birth certificates.

‘Since 2022, the members of this Association have convinced the parents of 430 children to take the administrative steps to obtain the missing birth certificate,’ explained El Hadji Mbengue, the project coordinator. ‘They accompany the parents to the mobile court hearings, where a court magistrate issues the certificates. These children will therefore have the chance to sit their primary school leaving exams and continue their studies in secondary school, instead of giving up and starting work’. Since the 2023-2024 school year, the Senegalese unions affiliated to EI have also had the active support of the imams of Bambilor in their advocacy for education, including the need to register all children at birth.

Ensuring access

School fees are a major obstacle to keeping children in school for the poorest families. In Zimbabwe and India, hundreds of children have been able to enrol in school since 2021 in the project areas of EI affiliates because the trade unions have disseminated information on the existence of government aid programmes for the most disadvantaged children: payment of school fees in Zimbabwe via BEAM (Basic Education Assistance Module), provision of uniforms and school equipment in India (with also, in India, other types of aid for girls in certain states). Local populations are often unfamiliar with these programmes, but hundreds of children have been able to benefit from them thanks to the support of teachers and community leaders trained by the trade union projects.

Education International advocates for government funded free quality education accessible for all, and believes schools fees should not interfere with the right to education.

Chiedza, aged 14, has been able to return to her school in Arambira (Zimbabwe): ‘I left school in 2021 because of the school fees. I lived with my mother and stepfather, but he was not interested in my education. My mother sent me to work as a maid 15 km away from my village. The work was heavy: I washed the clothes of three children and two adults, and cleaned the house from 4am to 9pm, six days a week. I was paid 50 dollars a month, and the money was sent to my mother. When the union project started, someone who had followed the training programme spoke to my mother, told her I could go back to school and advised her to speak to the headmaster on her behalf. My mother was told to speak to the local BEAM representative. As a result, I was readmitted to the school I had left in 2021. I was very happy to go back to school: for three years, I had seen the other children go, but I was deprived of it, I had to work’.

In Zimbabwe, the schools that are part of the ZIMTA and PTUZ unions' projects to combat child labour have also received a small grant that has enabled them to develop an income-generating activity, such as raising chickens and pigs. These activities are co-managed by teachers, pupils and members of the school management committees. The small profits are used to prevent the most disadvantaged children from dropping out of school (purchase of uniforms, exercise books, lesson books) or to strengthen school canteens. The possibility of having a meal at school is a major attraction for children from the most vulnerable families, especially since a drought worsened malnutrition in Zimbabwe in 2024. Teacher union projects supported by EI in Togo, Malawi and Uganda have also helped to develop school canteens.

A special focus on girls

The unions include in their projects actions to ensure that schools are welcoming to girls, who are more likely to drop out. In Uganda, for example, UNATU has trained teachers in gender equality in education, focusing on school safety and gender-based violence in schools. The union also draws attention to the vocabulary and stereotypes that can undermine gender equality. Hygiene management during the menstrual period is reinforced. ‘Most families cannot afford to buy sanitary towels in the regions where we are developing our projects to combat child labour,’ explained Gowan Kalamagi, coordinator of UNATU's projects to combat child labour. ‘During their periods, girls feel ashamed when they bleed, so they prefer to stay at home. The more they miss lessons, the harder it is to keep them at school, to interest them in the lessons, and so they risk dropping out. UNATU trains teachers to sew sanitary towels with their pupils, using readily available raw materials’.

The unions are also lobbying to ensure that there are separate toilets for girls and that every school employs at least one female teacher who can act as a confidante for the girls. In Uganda and Mali, the teachers and community leaders which the unions have involved in their projects have organised the children into groups so that they no longer make the journey to school alone, which can be dangerous for a girl on her own.

Reintegrating children after a long absence

The return to school of children who have worked and lived in the adult world for years often poses difficulties for teachers. Some are too old for the level of education to which they are entitled and risk becoming discouraged (for example, a 13-year-old who left school in the second year and finds himself in a class with 7- or 8-year-olds).

Others, after having come into contact with the adult world of work, have adopted behaviour or language that is not suited to the school environment. Most trade union projects provide for a period of adaptation for these children, for example in the form of refresher courses. In Zimbabwe, the PTUZ union has developed training for teachers who become specialised in looking after former child workers. According to Hillary Yuba, coordinator of the PTUZ project: ‘These teachers are then able to assess the former child worker as a whole, i.e. his or her cognitive, social and emotional development. They then give individual attention to the specific needs of each child. As a result, children who return to school feel loved, are more open to the school environment and want to stay there’.

- The 15 countries where EI affiliates are or have been supported in projects to combat child labour are Albania, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Côte d'Ivoire, India, Malawi, Mali, Morocco, Nicaragua, Senegal, Togo, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda and Zimbabwe. The main partners in these projects are AOb, Mondiaal FNV, Hivos and the Stop Child Labour Coalition (Netherlands), and the GEW Fair Childhood Foundation (Germany).