Joining forces for public education: Demystifying public-private partnerships

A new position paper and policy brief from the Privatisation in Education and Human Rights Consortium shed new light on the way in which public-private partnerships in education operate, the gaps between theory and practice, and the strategies that governments and educational institutions can employ to strengthen free, public education for all.

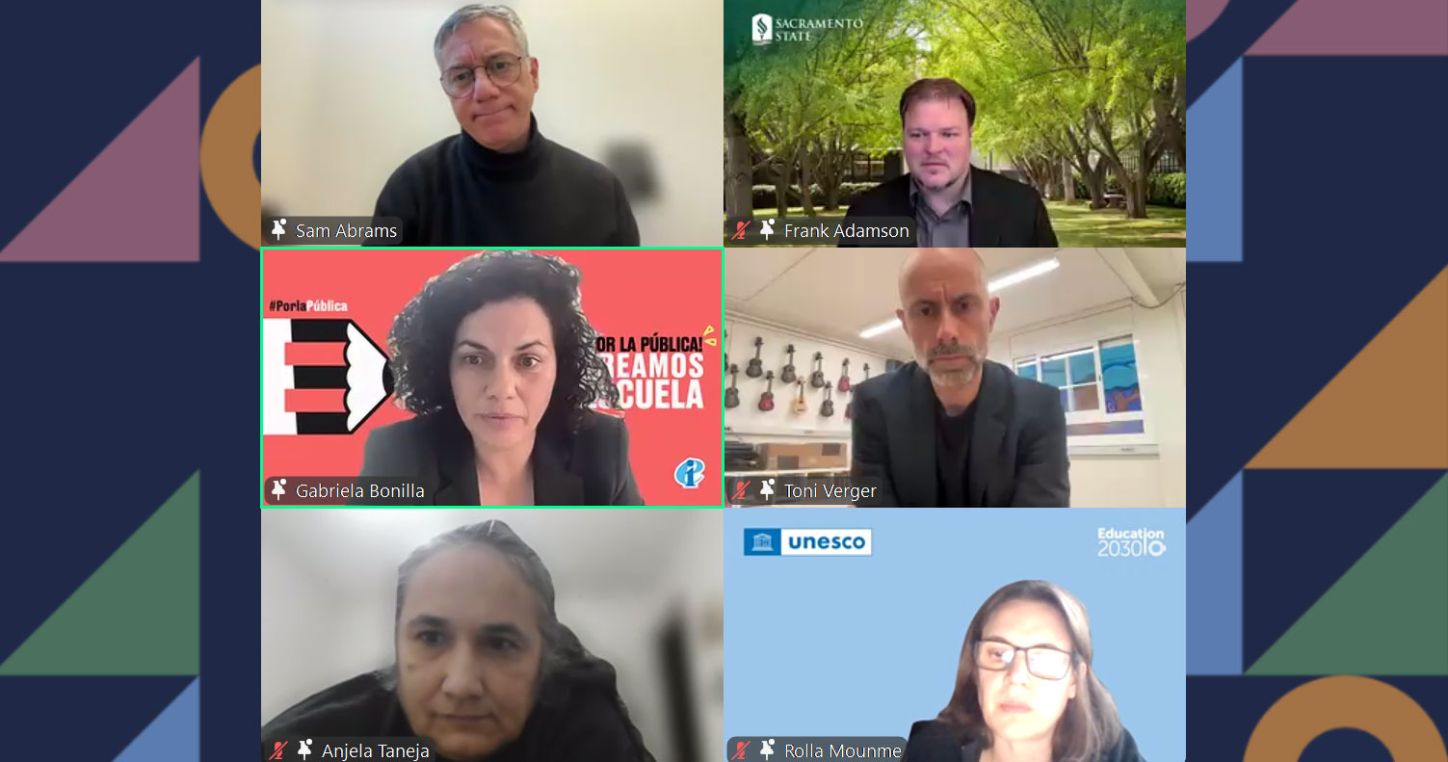

The lack of government funding for public education is often ostensibly mitigated by partnerships with non-state actors in the funding and provision of education. Entitled “ Demystifying Education Public-Private Partnerships: What Every Policy Maker Should Know”, the new policy brief and position paper explore the challenges presented by public-private partnerships, highlighting the common pitfalls in their implementation and the lack of stringent regulation to ensure that they do not negatively impact public education systems. Launched during a global online event on January 30, the policy brief aims to support more informed and strategic decision-making regarding public-private partnerships in education, protect public resources, improve policy implementation and enhance accountability.

“The idea that public-private partnerships can deliver quality education services with less funds is a myth. The truth is that public-private partnerships do not deliver quality, but they do profit from public funds. In parallel with the budget-cuts for public education that damage educational systems, there is a subtle operation to capture those public resources and put them at the service of business groups. We must therefore also discuss the use of public funds and why public money is going to the private sector,” emphasised Gabriela Bonilla, Education International Regional Director for Latin America, at the event that launched the new position paper and policy brief.

Bonilla also noted that public-private partnerships are nourished by the neoliberal myth that all public systems have failed and that the state itself is a failed actor. Constant attacks on the public sector and reputational attacks against teachers and public workers serve the business interests of groups that sell services to the state. Criticisms and systematic assessments are directed towards teachers and the education system, but no accountability is demanded from the private actors who have been involved in education for decades through public-private partnerships.

Furthermore, public-private partnerships serve governments that do not respect freedom of association and reject social dialogue with education unions. In these cases, education authorities are eager to replace teacher unions with NGOs, private companies, and foundations to implement part of the educational policy. Even governments that respect the rule of law have normalised the outsourcing of education policies, which creates a constant transfer of public funds and responsibilities to the private sector.

Having teachers take part in designing and defining education policy and pedagogical strategies, based on the knowledge they build every day in their classrooms, is critical to the quality of education delivered, as highlighted by the United Nations Recommendations on the teaching profession.

“Through our Go Public! Fund Education campaign, Education International is committed to building partnerships in order to defend tax justice, encourage public debt forgiveness, and safeguard the state as the actor responsible for public education”, Bonilla concluded.